Liberté chérie was a Masonic Lodge founded in 1943 by Belgian Resistance fighters and other political prisoners at Esterwegen prison camp. It was one of three lodges founded within a Nazi concentration camp during the Second World War.

In 1925, Adolf Hitler, the leader of Germany’s Nazi Party doubled down on enduring claims that the Jews were utilising Freemasonry to achieve their political end. The Catholics had long used the rhetoric that during the eighteenth-century Freemasons were instrumental in being a threat to Church and State, with the French Revolution a testimony to their claims. So, it was no surprise that in the following years, antisemitic and anti-Masonic sentiments continued to boil. In 1903, sections of a text called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fabricated antisemitic “expose” was serialised in the Russian newspaper Znamya (The Banner). Dangerously inflammatory, ‘The Protocols’ described a purported Jewish plan for world domination and built on previous works by Jesuit priests and antisemites whose narrative accused Enlightenment Freethinkers, Masons, and the Bavarian Illuminati of conspiring with the Jews to manipulate the global economy, politics, and religion for their own nefarious means.

Two years later it was published as an appendix to “The Great in the Small: The Coming of the Anti-Christ and the Rule of Satan on Earth”, another rabidly antisemitic text written by the Russian writer and mystic Sergei Nilus. Russia at the time was involved in ethnic cleansing of the Jewish communities, antisemitic sentiment was high, so it was unsurprising that ‘The Protocols’ was not put under critical scrutiny and via various channels, was translated and rapidly spread to the wider world. Even though the text was exposed by The Times of London as a fake, it was to have a catastrophic effect on both Jews and Freemasons.

In Hitler’s political diatribe “Mein Kampf”, he stated that:

To strengthen his [i.e., the Jew’s] political position, he tries to tear down the racial and civil barriers which for a time continue to restrain him at every step. To this end he fights with all the tenacity innate in him for religious tolerance—and in Freemasonry, which has succumbed to him completely, he has an excellent instrument with which to fight for his aims and put them across. The governing circles and the higher strata of the political and economic bourgeoisie are brought into his nets by the strings of Freemasonry, and never need to suspect what is happening.

In January of 1933, Hitler was appointed as German Chancellor and within months the arrest of political opponents began. On 20 March, SS leader Heinrich Himmler, announced the commencement of internment for political dissidents. Even before the genocide of the Jews gained momentum, the Nazis had begun rounding up political prisoners from both Germany and German-occupied Europe. Most of these prisoners were of two sorts: political prisoners of personal conviction or belief whom the Nazis deemed in need of “re-education” to Nazi ideals, or leaders of the Resistance movements in occupied western Europe.

Freemasons, alongside the other “undesirables” – the Jews, the disabled, homosexuals, Roma gypsies, and a long list of political dissenters – were to suffer an appalling fate. Millions were exterminated by the Nazis. Those classified as political internees (including Freemasons), were distinguished within the camps by an inverted red triangle sewn on the tunic.

The number of Freemasons who were sent to the camps and never returned is estimated to be between 80,000 and 200,000.

The Nazis rejected Freemasonry, banning it in January 1934, partly because it was associated with Jews.

The secrecy associated with Masonic rituals has always made the organisation susceptible to conspiracy theories. The Nazis believed that the Freemasons were part of a conspiracy working against the interests of German nationalism. Criticism of Freemasons was a regular theme in Nazi propaganda – often framed in antisemitic discourse about the threat from ‘World Jewry’.

Thousands of Freemasons were persecuted by the Nazi regime and many were imprisoned in concentration camps, classed as political prisoners.

[Source: Holocaust Memorial Day Trust]

Between 1933 and 1945 the Nazi regime operated over a thousand concentration camps on its own territory and within German-occupied Europe. It was in three of these camps that the only known Masonic lodges were founded and operated by inmates: Loge Liberté Chérie , Les Frères Captifs d’Allach, and L’Obstinée.

The first SS concentration camp was opened in Dachau near Berlin on 22 March 1933. From an initial count of 151 prisoners as of 31 March, the number rose swiftly to over 2000 by the end of June the same year. Camps began to spring up across the country; after Dachau, a second camp was opened in Esterwegan, located in the northwest Emsland district of Germany. At its height in 1944, Esterwegen housed over two thousand so-called political Schutzhäftlinge (protective custody prisoners) and was for a time the second largest after Dachau.

Officially, Esterwegen was not considered as a concentration camp but as a “Strafgefangenenlager” – “punishment camp for prisoners”. Of course, the living conditions in this camp were the same as in the concentration camps: tortures, executions, forced work in the swamps until death, etc… One of the most famous prisoners of Esterwegen was the German writer Carl Von Ossietzky. As pacifist and Nazi opponent, Carl von Ossietzky was jailed at Esterwegen several months after he received the Nobel Prize of Peace in 1936.”

[Source: Jewish Virtual Library]

Carl von Ossietzky.

Publizist, als Häftling in einem Konzentrationslager Esterwegen. Carl von Ossietzky in Esterwegen concemtration camp, 1934. Credit: By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R70579 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5368506

However, in December 1941, Hitler ordered a directive targeting political activists and resistance “helpers” in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany. Known as the Nacht-und-Nebel-Erlass (“night and fog directive”) it ended any compliance with the Geneva Conventions by abandoning “all chivalry towards the opponent” and removing “every traditional restraint on warfare.”

On 7 December 1941, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler issued the following instructions to the Gestapo:

After lengthy consideration, it is the will of the Führer that the measures taken against those who are guilty of offenses against the Reich or against the occupation forces in occupied areas should be altered. The Führer is of the opinion that, in such cases, penal servitude or even a hard labor sentence for life will be regarded as a sign of weakness. An effective and lasting deterrent can be achieved only by the death penalty or by taking measures which will leave the family and the population uncertain as to the fate of the offender. Deportation to Germany serves this purpose.

The Three Historic Lodges

Three known Masonic lodges were created in the camps, sadly the information for L’Obstinée and Les Frères captifs d’Allach is not as extensive as for Liberté Chérie.

L’Obstinée

Aptly named, L’Obstinée (“The Obstinate”) was founded in the German prisoner-of-war camp Oflag XD. The Lodge was founded by members of the Grand Orient of Belgium. Jean Rey, who would become President of the European Commission, was orator of the lodge. The Grand Orient of Belgium would recognize the Lodge on 14 July 1946.

By Marcelle Jamar – https://audiovisual.ec.europa.eu/en/photo-details/P-010705~2F00-1, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=112965097

Les Frères captifs d’Allach (the captive brothers of Allach)

The lodge was created in Allach, a sub-camp annexed to Dachau. It was primarily used as a labour camp, established on February 22, 1943 to address workforce shortages in the armament and building industry of Nazi Germany. Allach was considered the most important commando in the Dachau concentration camp. The deportees, of which numbered around 3850, worked there on various sites, mainly for the BMW factory.

On May 6, 1945, a group of Freemasons, created a Masonic lodge within the Allach camp. One of the known members of the lodge was Georges Dunoir, a member of Le Coq enchaîné (The Chained Rooster) a resistance group in the region of Lyon, under the Vichy regime and German occupation. Dunoir was arrested in 1942, deported to Dachau and then to Allach where he founded a lodge.

[Source: Museum of Resistance]

The Museum of Freemasonry in Paris has a vitally important piece of history concerning Les Frères captifs d’Allach – a register of the lodge workings showing the date of its creation. In an entry dated 6 May 1945, after their liberation by Allied forces, there is a list of members, an acknowledgment of themselves as “French-speaking international lodge”, and they pay tribute to the memory of brother [FD] Roosevelt, who had died on 11 May that year.

Paper, ink, 210 x 168 mm (open: 324 mm)

Paris, Museum of Freemasonry. Num. Inv. P4.003

© Museum of Freemasonry – all rights reserved.

The contents of the book explained:

The architecture book is a register that contains all the minutes of a Masonic meeting. The Freemasons use in their language and their rituals all the technical terms of architectural construction (example: the mason makes a board instead of saying that he is making a communication) while they appropriate the tools that they use as symbols of reflection for a personal construction (the compass, the square, the ruler, the plumb line, etc.).

This first page of the architecture book of the camp of Allach (kommando of Dachau) mentions the creation of an international lodge of French language which takes as name “Les Frères captifs d’Allach”. During this founding meeting of May 6, 1945, the brothers Roess (Venerable), Schmidt (Speaker) and Dunoir (Secretary) were elected as members of the office. It is important to point out that only two Masonic lodges have been identified within the concentration camps, the second, called “Darling Freedom”, having been founded by Belgian deportees at the Esterwegen camp.

This text contains many Masonic abbreviations. The abbreviation can be done in two ways: if the initial suffices for understanding, the initial of the word is written in capital letters and it is followed by three points in a triangle. In other cases, in order to avoid any confusion, we use the first syllable of the word with a capital initial, followed by the first consonant and three dots in a triangle.

The abbreviations used in this document are as follows:

F ..M .. = Francs-maçons

L .. = Loge

Int .. = internationale

Frat.. = fraternellement

FF .. = frères

Trav.. = travaux

Atel .. = atelier (synonyme de loge)

Ven .. = Vénérable (président d’une loge)

Orat .. = orateur

Secret .. = secrétaire

F ..M .. = Freemasons

L.. = Lodge

Int .. = international

Frat.. = fraternally

FF.. = brothers

Trav.. = works

Atel .. = workshop (synonymous with lodge)

Fri.. = Venerable (president of a lodge)

Orat .. = orator

Secret .. = secretary

During this meeting, the workshop pays homage to the American president, Franklin Roosevelt, who died on April 12, 1945, and who had joined Freemasonry in 1911. Warm congratulations are then addressed to the American brothers and allies for “the rapid success of our liberation. The brothers of the workshop then invite them to join in their work. The meeting ends with the agenda for the following meeting scheduled for Saturday, May 9, 1945 and having as its agenda “Improvement to be made to the organization of the camp”.

[Source: Fabrice Bourree, www.museedelaresistanceenligne.org]

Loge Liberté Chérie

However, of the three lodges created in the camps during those dark years, it is Loge Liberté Chérie that is the brightest light known to us. Two surviving members and several witnesses were able to give their accounts, and after years of painstaking research their stories have been recorded for posterity.

Esterwegen Camp – Barrack 6

On Friday 21 May 1943, the first convoy of the NN (Nacht und Nebel/Night and Fog) political prisoners arrived at one of the Emslandlager camps .

Among the first arrivals at Emslandlager VII (Esterwegen) were members of the Belgian Resistance, amongst them were Franz Rochat, Jean Sugg, Guy Hannecart, Paul Hanson,and Fernand Erauw.

Four of the men (Rochat, Sugg, Hannecart and Hanson) were Master Masons, they were placed together in Barrack 6 at the camp. As political dissenters (which included Freemasons) they would have been assigned the ‘red triangle’ emblem stitched to their uniforms.

At its height in 1944, the Esterwegen concentration camp housed over two thousand political prisoners from occupied Europe. By some twist of fate, this small group of Belgian Freemasons found themselves in the same barrack. They soon came together to form a group and when the number of Master Masons within the cramped hut reached seven, they were able to form a lodge. A remarkable and highly dangerous achievement that would help the men bolster their resilience in horrendous circumstances.

An invaluable resource for information on the Lodge is to be found on a blog dedicated to Maurice Orcher (1919-1944), a Belgian Resistance fighter and martyr, executed by the Nazis. Maurice had been sent to Esterwegen along with fellow Belgian Franz Bridoux. In 1941, Franz had joined the resistance organization the “Rassemblement National de la Jeunesse RNJ” – youth section of the Front de l’Indépendance – FI. After mass arrests on resistance members by the Brussels Gestapo in 1943, he and Maurice found themselves in Barrack 6 at Emslandlager VII.

Bridoux escaped from a death march in 1945, and later contributed his testimony to the Maurice Orcher blog. His full account of life in Barrack 6 and Loge Liberté Chérie was then published in his book “Liberté Chérie in Nacht und Nebel Gründung einer Freimaurerloge im KZ Esterwegen” (“Liberté Chérie in night and fog – Founding of a Masonic lodge in the Esterwegen concentration camp”).

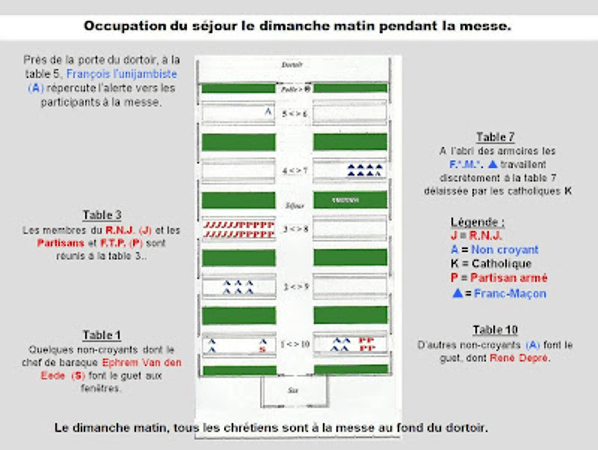

Franz Bridoux recalls that Barrack 6 was occupied by:

…national and regional leaders of the RNJ, Freemasons, Socialists, Catholics, who were also later joined by French prisoners who were members of the FTPF (francs-tireurs partisans français) …the simple wooden barracks divided into zones: the refectory, the dormitory and the toilets. The tables are organized into groups J (for RNJ), K (for Catholics), S (for socialists), and Freemasons…the groups are reconstituted, and life is organized around large tables. The work there is useless and humiliating, we sort casings that the Germans mix again in the evening. The food is insufficient and the prisoners lose 5 kg per month.” [translated from the French]

More than a hundred prisoners were in Barrack 6 and locked up nearly around the clock — allowed to leave only for a half-hour walk per day, under supervision. During the day, half of the camp had to sort cartridges and radio parts; at the end of the day, the guards would throw all the sorted parts into one box and the prisoners would sort them again – a pointless and dehumanising task. The prisoners in the other half of the camp were forced to work under dreadful conditions in the surrounding peat bogs.

Franz was only 20 years old and had no previous knowledge of Freemasonry. However, he quickly became friends with the Freemasons who shared table 3 with him, his companions from the National Committee of the RNJ and other French prisoners who were members of the FTPF (francs-tireurs partisans français). “At Table 3, several FMs are present: L. Somerhausen, P. Hanson, G. Hannecar, F. Rochat, J. Sugg and A. Miclotte. Also present are members of the RNJ: S. Goldberg, F. Lecoq, J. Lagneau, A. Verneirt, A. Steux and J. Berman.”

Franz continues:

In the barrack there are soldiers, civil servants, doctors, lawyers, journalists, priests, teachers, students, merchants, workers, aristocrats ….

The grouping at the tables is done by linguistic affiliation, by affinity and by organization of resistance. Catholics tend to get closer to priests and in the evening chant collective prayers aloud. Believers are much more numerous and on Sunday mornings, they meet at the back of the dormitory for mass.

Non-Catholics and non-believers stand guard and serve as screens for believers.

Although not a member of Loge Liberté Chérie, Franz witnessed the workings of the lodge, held at one of the tables whilst the Mass was taking place; the area was “relatively isolated thanks to the cupboards which separate them.” The Catholics shielded the Masons and vice versa; in adversity there was no distinction, no prejudice, nor intolerance. It was testimony to the principles of Freemasonry, that all should be equal, on the level. The humanity and compassion of the inhabitants of Barrack 6 transcended the external hate and intolerance that was sweeping Europe.

Cherished Liberty

The second convoy of inmates arrived on May 28, 1943. As new prisoners arrived, so did the number of Freemasons increase until there was the requisite seven Master Masons to create a lodge. It was the arrival of Master Mason Amédée Miclotte that finally allowed the lodge to be formed, and on 22 November 1943, within the darkness of a Nazi prison camp was born the light of Liberté Chérie – “Cherished Liberty”.

They chose the name partly in reference to the French national anthem La Marseillaise, an appropriate choice in more ways than one as the song had its roots in Freemasonry – and of course, liberty. Around 24/25 April 1792, Freemason Captain Rouget de Lisle Baron, was the guest of Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich, mayor of Strasbourg and worshipful master of a local Masonic lodge. At Dietrich’s behest Rouget de Lisle Baron wrote “Chant de guerre pour l’Armée du Rhin” (English: “War Song for the Army of the Rhine”), and dedicated the song to Marshal Nicolas Luckner, a Bavarian freemason – a song to “rally our soldiers from all over to defend their homeland that is under threat”. That song would soon become the Republican anthem of the French during the Revolution.

Another reason the name of the lodge was chosen was to honour the protest song “Die Moorsoldaten” – the Peat Bog Soldiers, a song written in 1933 in the nearby Emsland camp of Börgermoorby by Communist prisoners Johann Esser (a miner) and Wolfgang Langhoff (an actor); the music was composed by Rudi Goguel. It was first performed by the prisoners at a Zircus Konzentrani (“concentration camp circus”) on 28 August 1933 and soon became a favourite of oppressed workers throughout Europe. The song has a slow simple melody, reflecting a soldier’s march, and is deliberately repetitive, echoing and telling of the daily grind of hard labour in harsh conditions. The “Le Chant des Marais” is the French translation of “Die Moorsoldaten”.

Members of the Lodge

Paul Hanson (1889 – 1944) Lodge Master and Founder Member – Justice of the Peace in the canton of Louveigné, active in an intelligence and action service and member of the Loge Hiram in the Orient of Liège. Hanson was moved from Esterwegen to one of the camps in Essen, and died in the rubble of his prison, during the Allied air bombardment on Essen, on March 26, 1944.

Luc Somerhausen (1903–1982) Founder Member – a journalist, born on 26 August 1903, in Hoeilaart. He was arrested on 28 May 1943 in Brussels. He belonged to the lodge Action et Solidarité No. 3 and was deputy secretary of the Grand Orient of Belgium. As Luc knew the Masonic procedure to follow, he was instrumental in the creation of Liberté Chérie, as writer of the statutes. After liberation, he obtained official recognition of the lodge from the Grand Orient of Belgium. Luc died in Brussels on April 5, 1982.

Jean Sugg (1897-1945) Founder Member – born in Ghent and was of Swiss German origin. He co-operated with Franz Rochat in the underground press, translated German and Swiss texts, and contributed to clandestine publications, including, La Libre Belgique, La Légion Noire, Le Petit Belge, and L’Anti Boche. Jean belonged to the Philanthropic Friends Lodge Les Amis Philanthropes, Lodge No. 5 of the Grand Orient of Belgium. He died in Buchenwald concentration camp on May 6, 1945.

Amédée Miclotte (1902-1945) Founder Member – a high school teacher. He was born 20 December 1902 in Lahamaide, and belonged to the lodge Union et Progrès. He was last seen in detention in Gross-Rosen concentration camp on 8 February 1945.

Franz Rochat (1908-1945) Founder Member – a professor, pharmacist, and director of an important pharmaceutical laboratory, was born on 10 March 1908 in Saint-Gilles. He was a worker in the underground press, and the resistance publication Voice of the Belgians. He belonged to the Philanthropic Friends lodge les Amis Philanthropes, Lodge No. 5 of the Grand Orient of Belgium. He was arrested on 28 February 1942. After his time in Esterwegen, he was moved to Untermassfeld in April 1944, and died there on 6 April 1945.

Guy Hannecart (1903–1945) Founder Member – a lawyer and leader of La Voix des Belges. He was also member of the lodge les Amis Philanthropes. Guy died in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on 25 April 1945.

Joseph Degueldre (1904-1981) Founder Member – doctor, member of “Travail” lodge of Verviers and member of the Secret Army (Belgium). He was seated at table 2 with a group of resistance fighters from his region but participated in the work of the lodge on Sunday mornings. Joseph died in Pepinster on April 19, 1981.

Jean De Schrijver (1893- 1945) Affiliate Member – a colonel in the Belgian Army. He was born 23 August 1893 in Aalst, and was a brother of the lodge La Liberté in Ghent. On 2 September 1943 he was arrested on charges of espionage and possession of arms, he died on 9 February 1945, in Gross-Rosen concentration camp.

Henri Story (1897-1944) Affiliate Member – a Belgian businessman and liberal politician from Ghent, Belgium. His work for the underground resistance during the war would lead to his capture and death. He was a member of lodge Le Septentrion. On 22 October 1943 he was arrested in his office at the Kouter in Ghent. Attempts to get him released failed and in March 1944 he was transported to Germany. Story died in the camp at Gross-Rosen near Breslau on 5 December 1944.

Fernand Erauw (1914-1997) – an assessor at the Audit Office, and reserve officer with the Infantry, was born on 29 January 1914, in Wemmel. He was arrested on 4 August 1942, as a member of the Secret Army. He escaped and was finally arrested in 1943, arriving at Esterwegen. Shortly before the departure of Luc Somerhausen on February 22, 1944, Fernand was initiated, then raised to the third degree. Erauw escaped the death marches with Somerhausen. He died in Ottenbourg on 8 April 1997.

From Franz Bridoux’s testimony:

Luc Somerhausen described Erauw’s initiation, etc., as just simple ceremonies. These ceremonies (in the maintenance of the secrecy of which, they asked the community of Catholic priests for assistance, “with their prayers”) “took place at one of the tables …after a very highly simplified ritual—whose individual components were however explained to the initiate; that from now on he could participate in the work of the Lodge”.

After the first ritual meeting, with the admission of the new brother, further meetings were thematically prepared. One was dedicated to the symbol of the Great Architect of the Universe, another to “the future of Belgium”, and a further one to “the position of women in Freemasonry”. Only Somerhausen and Erauw survived detention, and the lodge stopped “working” at the beginning of 1944.

The Survivors

From Franz Bridoux’s testimony it is known that Erauw and Somerhausen survived. They were moved from Emslandlager VII, but met again in 1944 at Sachsenhausen concentration camp and remained inseparable from then on.

In 1945, as the Germans faced defeat, prisoners were moved via death marches from the camps to evade the approaching Allied Forces. Miraculously Somerhausen and Erauw survived the ordeal. After repatriation, Erauw, although 1.84 m tall, weighed only 32 kg on 21 May 1945 when treated in the Saint Pierre Hospital in Brussels.

In August 1945, Luc Somerhausen sent a detailed report to the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Belgium, in which he delineated the history of the lodge. It was through his testimony that official recognition by the Grand Orient of Belgium was obtained for Loge Liberté Chérie. Somerhausen died in 1982 at the age of 79.

Fernand Erauw died at the age of 83, in 1997. Up until his death, Fernand Erauw’s wish was for us to relentlessly track down “all forms of oppression, all forms of negation of the human being, all cowardice, all fascism, all totalitarianism…”

Doctor Joseph Degueldre also survived; he died in Pepinster, Belgium in 1981 where there is a plaque dedicated to him.

In the spring of 1945, Franz Bridoux and three other regional leaders of the RNJ: Joseph Berman, Marius and Marcel Cauvain were transferred to the prison of Ichtershausen (Thuringia). Shortly after they were sent on a death march towards the mountains of Upper Silesia. They escaped together to Pösneck on 11 April 1945, where they were liberated by the American army on April 15 and repatriated on 7 May 1945.

The Esterwegen Memorial

By de:user:Marvins21 – de.wikipedia.org – upload by the author, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=957003

A memorial dedicated to those brave men, created by architect Jean de Salle, was raised by Belgian and German Freemasons on 13 November 2004. It is now part of the broader site of the Esterwegen Memorial, a place of remembrance for all 15 Emsland camps and their victims.

Wim Rutten, the Grand Master of the Belgian Federation of the Le Droit Humain gave the following address:

We are gathered here today on this Cemetery in Esterwegen, not to mourn, but to express free thoughts in public.” – “In memory of our brothers; human rights should never be forgotten.

By de:user:Marvins21 – de.wikipedia.org – upload by the author, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=956997

Franz Bridoux – the man who lifted the fog

Via http://freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/Libert%C3%A9_ch%C3%A9rie

Franz Bridoux became a Freemason after the war, he died on 14 January 2017 at the age of 94.

Read a memorial here from the Masonic blog Under the Starry Vault, and view his incredible testimonies on YouTube:

Témoignage de Franz Bridoux part 2

Au camp de concentration d’Esterwegen – Franz Bridoux

“Nuit et Brouillard” au camp de concentration d’Esterwegen. Travail de mémoire de Franz Bridoux.Musique : “Le Chant des Marais”.

Under the Starry Vault blog made a moving tribute to Franz, with images from his book, and the song “Le Chant des Marais”.

*This article was originally published in the Square Magazine (2023)

Acknowledgments:

Grateful thanks goes to Samy Benoudiz (Maurice Orcher – Resistant and Martyr blogspot) for permission to use text and images from Franz Bridoux’s testimony.

Sources

Maurice Orcher – Resistant and Martyr

This blog was created by the family and friends of Maurice Orcher, to perpetuate his memory.

http://mauriceorcher.blogspot.com/2009/01/cration-de-la-loge-libert-chrie-au-camp.html

Musee de la Resistance www.museedelaresistanceenligne.org

BnF http://expositions.bnf.fr/franc-maconnerie/grand/frm_195.htm

Wikipedia contributors, “Liberté chérie,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Libert%C3%A9_ch%C3%A9rie&oldid=1059712853 (accessed December 27, 2022).

Wikipedia contributors, “Esterwegen concentration camp,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Esterwegen_concentration_camp&oldid=1084910345 (accessed December 27, 2022).

Wikipedia contributors, “Nacht und Nebel,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nacht_und_Nebel&oldid=1097326677 (accessed December 27, 2022).

Wikipedia contributors, “L’Obstinée,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=L%27Obstin%C3%A9e&oldid=933799092 (accessed December 27, 2022).

Further Reading

Fernand Erauw: L’odysée de Liberté Chérie, 1993 — History of this Lodge (in French) https://bel-memorial.org/documents/liberte_cherie_Fernand_ERAUW.pdf

The extraordinary story of prisoners, during the 1940-45 war, in German concentration camps, interned for acts of resistance in the NN category (“Nacht und Nebel”), who recognize each other as being Franks-Masons. The rest is told by Fernand Erauw, the only Mason initiated in the Nazi camps, during his very captivity. [Source: Masonic site Acacia.fm, now defunct. This site was in its time organized by René Louis LESIMANT.]

La Respectable Loge Liberté Chérie au camp de concentration d’Esterwegen, Nuit et Brouillard by Franz Bridoux. Éditions du Grand Orient de Belgique 2009. French Language.

Liberté chérie, l’incroyable histoire d’une loge dans un camp de concentration by Franz Bridoux. Boite a Pandore (2014)

Liberté Chérie – Una Loggia Massonica Nel Campo di Concentramento di Esterwegen (1943-1944) Bastogi Libri (2016)

Loge Liberté chérie: A Light in the Darkness by Alexander P. Herbert

The Red Triangle: A History of Anti-Masonry by Robert LD Cooper

Leave a comment