Did you blink and miss it?

Phew, that’s UK Disability History Month over for another year and I’ll bet you are all thinking how relieved you are that you aren’t still being constantly bombarded with big brand companies changing their profile pictures, flying the disability flag, selling special sandwiches in our honour, or flooding social media with endless posts about how brave, stunning, and marginalised we are. I know I’m exhausted from just navigating it all!

Which would have been awesome if it had actually happened that way — except it didn’t — the above scenario is just a figment of my jaded imagination.

The sad truth is that nobody outside the disability communities cared. Corporations ignored it; hospitals and other public institutions barely acknowledged it. Where were they in imploring us to examine the centuries of often shameful history of disability and how disabled people have been bullied, tortured, victimised, or threatened with eugenical solutions to rid the world of us. It was a decidedly damp and disappointing squib of a month. The same happened with Disability Awareness Month in July.

UK Disability History Month (UKDHM) is held annually between 16 November-16 December – this year the theme was Disabled Children and Youth.

The UKDHM website was filled with information and resources around the subject — they declared that:

UKDHM 2023 provides an opportunity for all councils, service providers, education establishments, youth, play and sports organisations, health providers and employers* to examine their approaches to disabled children and youth. Those in the media, publishing and image making can challenge the way they have portrayed disabled people in the past and create inclusive and non-stereotypical ways forward, in conjunction with disabled young people.*

From a history of neglect, harsh punishment, segregation, bullying and ignorance we must learn to challenge our prejudices and discriminatory practices. The way disabled children and young people have been and are treated is an indicator of how inclusive and rights respecting we are as a community and society.

Impairment is a natural part of human existence, but societal responses have varied across cultures and time. Disabled people including children have often been falsely blamed and scapegoated for society’s ills. If one grows up on the receiving end of negativity, then one often internalises that negativity.

Most important in bringing about positive change is how we think about impairment and disablement.

*My bold

https://ukdhm.org/

Undeniably a worthy cause and a subject we should all be passionate about in an inclusive society, right? Well, if this year’s pathetic collective effort by the UK was anything to go by, I’d have to deduce that the answer to that is a big fat –‘nope’!

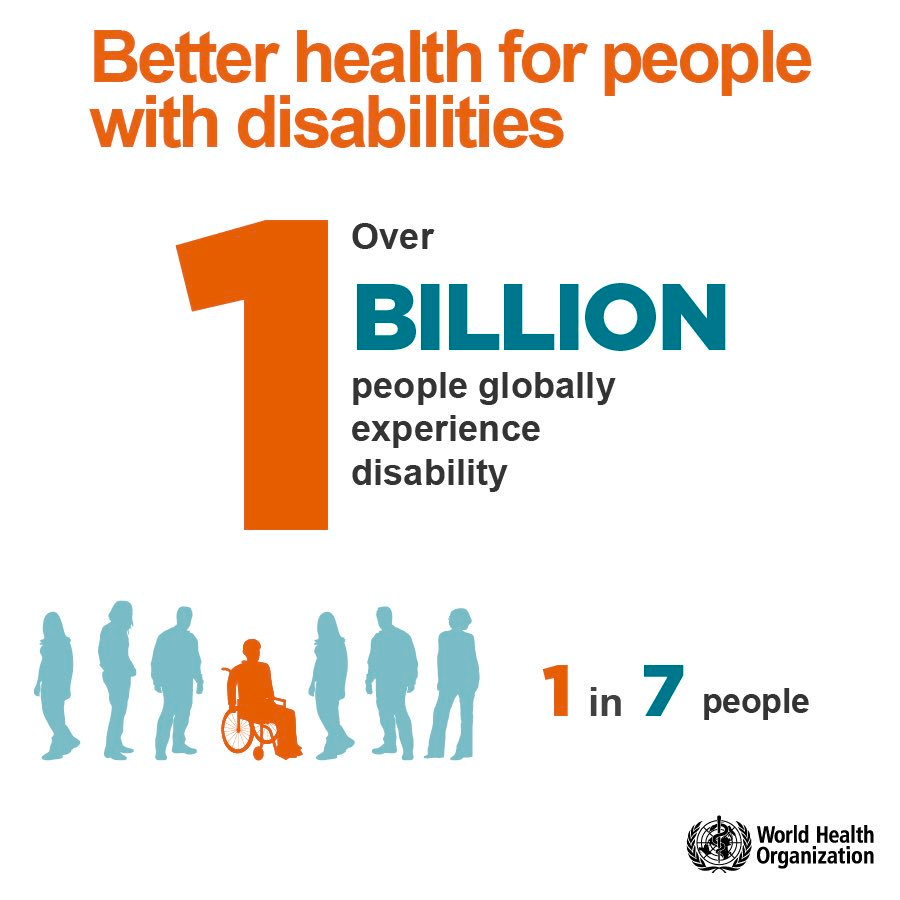

A BIG minority

Disabled people are one of the largest minorities on the planet — a bit of an oxymoron really but there is not another way of putting it. Yet, we are repeatedly left behind when it comes to the new shiny forums of ‘diversity and inclusivity’ that public sector organisations and institutions are so enraptured and captured by. A brief nod here and there to keep us appeased but in general there is very little headway in practical approaches or financial support.

Figures from Census 2021, the Family Resources Survey: financial year 2021 to 2022, and the UK Disability statistics: Prevalence and life experiences published in 2023 by the UK Government, illustrate that there are approx. 16.8 million people in the UK known to suffer from a disability — the UK Equality Act 2010 defines a disability as: a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities.

The King’s Fund takes all these figures and clearly shows how disabled people suffer on a daily basis, not only physically or mentally but financially:

Disabled people earn less and have higher living costs on average than those who are not disabled, so it is unsurprising that the cost-of-living crisis has had more of an impact on disabled people. 50 per cent of disabled people report that due to the rising cost of living, they are now spending less on food and other essentials, compared to 38 per cent of people who aren’t disabled. Evidence also suggests that disabled people wait longer for NHS treatment than those who aren’t disabled.

Source: The King’s Fund

The Social Model of Disability — and disappointment

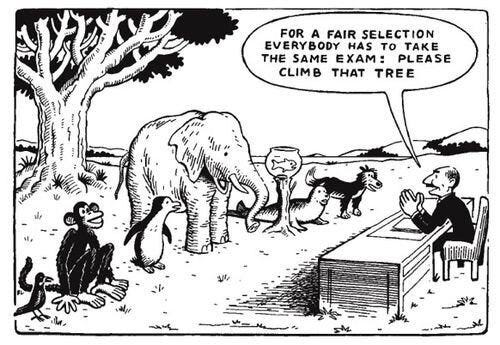

To understand the social difficulties for disabled people we need to look at the social model of disability, which was only conceived in the 1960s:

The social model of disability identifies systemic barriers, derogatory attitudes, and social exclusion (intentional or inadvertent), which make it difficult or impossible for disabled people to attain their valued functionings. The social model of disability diverges from the dominant medical model of disability, which is a functional analysis of the body as a machine to be fixed in order to conform with normative values.[1] While physical, sensory, intellectual, or psychological variations may result in individual functional differences, these do not necessarily have to lead to disability unless society fails to take account of and include people intentionally with respect to their individual needs. The origin of the approach can be traced to the 1960s, and the specific term emerged from the United Kingdom in the 1980s.

The social model of disability is based on a distinction between the terms impairment and disability. In this model, the word impairment is used to refer to the actual attributes (or lack of attributes) that affect a person, such as the inability to walk or breathe independently. It seeks to redefine disability to refer to the restrictions caused by society when it does not give equitable social and structural support according to disabled peoples’ structural needs.[2] As a simple example, if a person is unable to climb stairs, the medical model focuses on making the individual physically able to climb stairs. The social model tries to make stair-climbing unnecessary, such as by making society adapt to their needs, and assist them by replacing the stairs with a wheelchair-accessible ramp.[3] According to the social model, the person remains disabled with respect to climbing stairs, but the disability is negligible and no longer disabling in that scenario, because the person can get to the same locations without climbing any stairs.[4]

Text Source: Wikipedia; Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0

So, what do we want — or more politely, what would we like to see happen in the very near future?

I want to live in a world where we don’t have such low expectations of disabled people, that we are congratulated for getting out of bed and remembering our own names in the morning.I want to live in a world where we value genuine achievement for disabled people

Stella Young, Comedian and Disability Activist

Me personally? I’d like to see a normalisation of disability. There are millions of us with obvious physical disabilities (using crutches, sticks, wheelchairs etc), and an equally big percentage of ‘invisible’ ones — think hearing loss/deafness, bowel/bladder diseases and so on. But how many wheelchair users do you regularly see just buzzing around doing shopping, having a night out, or working in public institutions or businesses? Not many I’ll bet, and I can back that up because I am now not able to do those things with ease. Few shops, restaurants, pubs, or clubs are truly accessible — they do the basic mandatory adaptions (if at all) to comply with the Equality Act Reasonable Adaptions section i.e. an accessible (usually disgusting) toilet if you are lucky, and perhaps a ramp to get inside (rare). If you are hearing impaired it gets even worse but in different ways — people rarely acknowledge or engage with the issues surrounding hearing loss/deafness — they have no idea how frustrating, stressful, exhausting and sometimes downright dangerous everyday life can be.

But if you ‘haven’t got it, you won’t get it’.

That’s why disabled people need to be listened to — we should be the ones consulted when adaptions are considered, not some well-meaning but effectively clueless overpaid ‘diversity and inclusion’ officer who has no idea what it is actually like to live with a condition that hampers your daily life in so many ways.

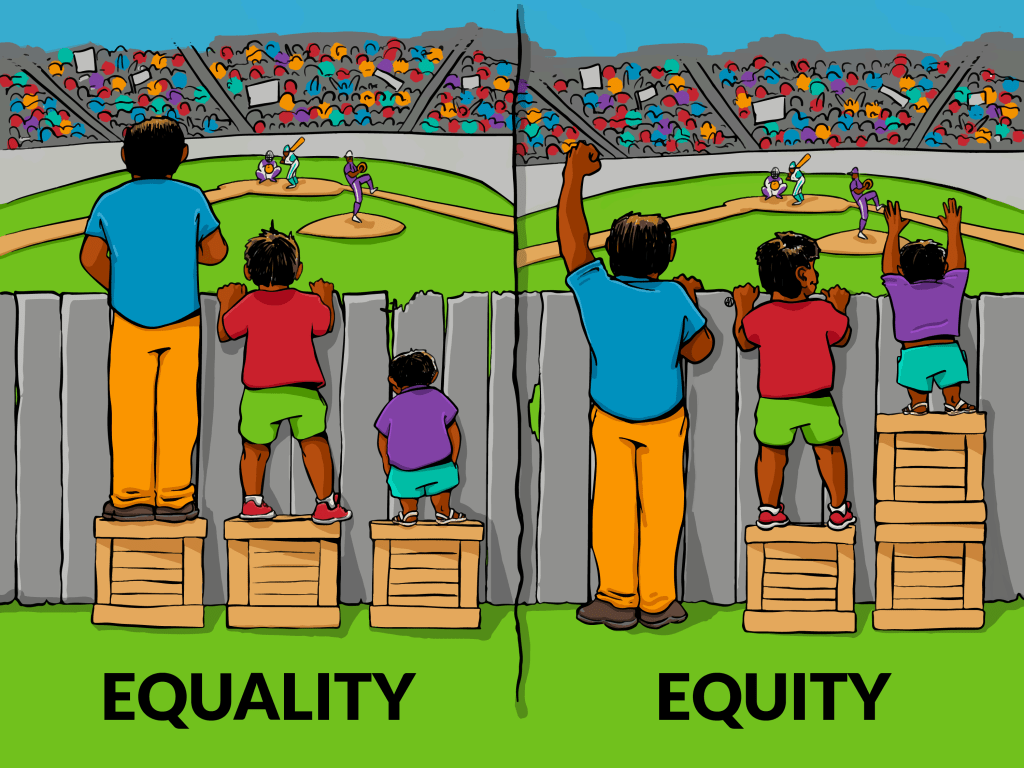

The majority of us don’t want to be perceived as ‘victims’ or as a burden or ‘leech’ on society; lots of us still work part-time, most often we are self-employed because that way we can adapt our working environment and hours to suit our conditions. But, for many, our conditions do impact our ability to do the things able-bodied folk take for granted on a daily basis. We just want the chance to be able to do — within obvious reality and reason — the things others can do. To participate in life; achieve equity in support and contribute to society in a positive way.

Not your inspiration, thank you!

What a lot of us don’t want (apart from social media ‘influencers’) is to be an ‘inspiration’ for those who can easily do the things they applaud us for — we just want to get on with life the best we can, without a metaphorical obstacle course in our way. Big events and gestures such as the Paralympics are great for raising awareness and for talented disabled athletes to excel — but that is just a small representation of very high-functioning disabled people. The reality is very different for many of us — we can’t live up to the expectation that disabled people should be endlessly inspiring ‘warriors’ for an able-bodied world, apart from being patronising crap, it’s bloody exhausting!

The late great comedian and disability activist Stella Young did this brilliant TEDX talk on society’s habit of turning disabled people into “inspiration porn.”

Let’s make real history — now!

Disability History Month is there to highlight the inequalities and discrimination that those with disabilities have faced — and are still facing — but it should also be a very important event to highlight how far we have come in what is a very short time since the Disability Acts were initiated and how much progress we should be making. I hereby set a challenge for all those virtue-signally companies and public sector think tanks — next year, step up and support those with disabilities.

We are making history all the time — don’t let it be seen in 50 years’ time that not much has changed and those whose physical or mental limitations are still being left behind.

Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire. Via: interactioninstitute.org

Further reading

Social Model of Disability by Clarence Henkhaus

The author is someone whose views are interesting particularly as he is not a sheep blindly following in a community that is increasingly being infiltrated by the hard left where different viewpoints are never tolerated.

As a disabled community if we ever got our act together we would be a block that could not be ignored much like pensions are now. There is a lot of us and if were are organized we could focus the minds of policymakers of all the political persuasion.

Positively Purple: Build an Inclusive World Where People with Disabilities Can Flourish by Kate Nash

For many people with a disability, either visible or invisible, that experience is hard to navigate in the context of work. Champion change, for yourself and others, challenge stigma and become Positively Purple.

Sharing a compelling personal story, Kate Nash offers practical advice for how employers can build environments of trust and support for those with disabilities, how employees with disabilities can advocate for themselves and flourish in the workplace and how those without disabilities can be true allies.

Leave a comment